It’s Day 17 in the hospital. A high point, in hindsight. It’s a day when I both leave my room and see my children. By this time I’m less likely to die suddenly from a brain bleed, and the shock of being torn from life has subsided. Just like the middle miles of a marathon, I’m in a groove. I’m cruising. Day 17 is as good as it gets in the hospital.

The bumpy start

Around 2am on January 16th, I’m rolled to my new home on the blood cancer floor. Steve is gone, and I’d already received chemo during the long wait for a bed. My eyes wander along the route as a headache starts squeezing and tightening around my brain, a pain I soon grow accustomed to battling.

The nurse stops the wheelchair in front of my new digs. I peer inside. Someone is in there. This is my room? I ask, looking up. The image of living in a shoebox with a cancer stranger throws another blow to my throbbing skull. I hunch over. I rest my elbows on my thighs and sink my eyes into my palms. “We’re at 120% capacity,” I hear through Squeeze. Pound. “Better than a hallway.” Pound. Throb. “The most immunocompromised get private rooms.” Press. Squeeze. ”You need the specially trained nurses on this floor.”

I quickly stop caring. I need a whopping dose of something for my head. I need to lie down.

New Jersey, my nickname for the roommate inside, is the best one I’ll have but I don’t know that yet. She’s a sweet 61-year old, quiet, no visitors, doesn’t snore and barely uses the bathroom. My arrival marks her penultimate night after 10 days in the hospital. Her previous stay was six weeks. One day I’ll be her, I think enviously. One day I’ll be the lucky veteran who gets to leave.

Marathon starts are always choppy too. It’s when I find out how my body’s showing up, and how the weather and race energy are working, or not. In the first few miles I have an uncomfortably full bladder and need to empty it somewhere, a stressful pursuit that adds precious time.

And this is where the cancer-is-marathon metaphor starts breaking down.

On marathon day, I’m in peak shape. My muscles are lean and hard and capable. My head is ready for the grind. I’m at the top of my physical and mental game. I planned months of training down to each day and workout. I’m there by choice, and I generally know when the pain is going to hit.

Cancer sends me to the hospital when I’m already weak in body and spirit. There has been no training. There has been no choice. Running 26.2 miles with zero preparation would be disastrous, if not impossible. That’s what this is though, but worse. I’ve been thrown into a 100-mile ultramarathon without even knowing it. I don’t even know what day it is or what’s coming next, nor where or what the finish line even is.

The night that New Jersey leaves, Long Island arrives. It’s around 1am when the storm blows through the door. The room turns bright and loud and chaotic, an assault on my senses. Half the state must be behind that curtain. Three people stay, squeezed into her cramped space, snoring, shifting, turning, talking, all through the night. I don’t sleep again. The next day, Long Island FaceTimes family during rounds and throughout the days that follow. There’s shouting, questioning, yelling, weeping, Her belongings and hairs litter the bathroom. She’s 55. She had fainted in her kitchen. She has seven lesions on her brain.

Don’t forget to change your shirt

After the first week, the shock dulls. I stop fighting my new reality. I stop looking at the weather forecast. I stop glancing at my calendar. I stop planning for the meeting. I stop thinking about which child has practice and how they’re getting there. I forget about the dinner party. It’s a slow breakdown of my old self. It’s a complete time warp.

I get a photo of Luke holding a giant pink bowl in the pediatrician’s office. His face is green. Steve has asked how he should clean the puke that’s all over the carpet. I don’t even care.

There are many days when the bathroom is my only accomplishment. Tethered to an IV and on crutches, I can’t just get up and go. There are so many steps. Socks on. Sit up. Hop to crutches. Crutch-IV to wall. Unplug IV. Hang cord on pole. Crutch-IV to curtain end. Detangle IV from curtain. Pull curtain. Crutch-IV to bathroom door. Open door. Crutch into bathroom. Pull IV into bathroom. Close door. Lean crutch on wall. Hop. Pivot. Pee. Retrace all steps in other direction. It’s a production. And with fluids flowing directly into my veins, I have to do this absurd exercise at least 10 times a day.

It’s day 8. I see him as I hobble into the bathroom at 2am. I yelp. Mr. C, my third roommate, is a dark brown leathery cockroach the size of a hamster, maybe the most gigantic insect I’ve ever seen. He is slowly roaming under the sink, his long wiry antenna extending his size.

I am groggy and foggy with arms literally tied up in tubes and cords, so all I can do is hobble back out of the bathroom. But I can’t avoid it for the next four weeks, so every time I go in I give the floor a onceover. I never see Mr. C again, both relieving and disturbing. Every day I wonder, if he’s no longer in the bathroom, where is he?

Showering is even more of a climb. I don’t do it very often. The PICC line in my arm and the biopsy dressing on my hip first need to be carefully wrapped—they can’t get wet. I need help finding and placing towels on the tiny plastic seat and on the floor for a makeshift bath mat. The dank stall is smaller than a phone booth so my knees nearly touch the sink. I don’t dare move the bunched up shower curtain—it seems too perfect a hideout for Mr. C. Water goes everywhere, every time.

Getting dry, dressed and back to the bed hooked to a million tubes with only one good leg is comical. I’m cold, wet and shirtless, since the shirt part requires a nurse. She eventually comes and weaves my old shirt free through each IV bag and tubing, and then threads my new shirt back through the same obstacle course.

Pennsylvania, my fourth roommate, doesn’t take one shower in the 10 days we live two yards from each other. I’m not judging. I get it.

Knitting and other things I never do

I can’t listen to music. Even Pink Pony Club. Especially Pink Pony Club. And it’s not just because it reminds me of that sad day in Target. That song, and too many others, remind me of my 4-inch-high-heeled self who loves a good dance party in someone’s kitchen. It reminds me of the me who likes to blast tunes while running the streets on two strong legs. I’m not sure I’ll ever be her again. Even dreaming about the most mundane moments of my life, music is gasoline on that fire. The boring beeping whirring sounds of the hospital are more bearable than music that moves me.

Reading? I thought so too which is why I grab my book the day I leave. But I soon chuckle at the absurdity of it, being able to lose myself in a novel. I can’t read. Period. I can’t watch shows or movies either. I try. I really try. I dabble in an audiobook and a couple of podcasts, but I am always too uncomfortable or too ill or too spaced out. It’s amazing how much time fatigue, headaches and nausea can consume.

Here’s what I do accomplish: vitals every four hours, even at 4am when I’m finally dozing after a night of restlessness. Wake up, Sit up. Arm out for cuff. Finger out for oxygen. Mouth open for temp. Then the 5am blood draw. The morning weigh-in. The pre-dawn meds. The morning meds. The daily EKG. The afternoon weigh-in. The chemo infusion. The evening meds. The bedtime meds. The dressing change. Each is a mini-nurse ritual, its own distinct disruption requiring gloves on, bracelet scan, name and birthday, clicks through chart, medication scan, pill dispense, bracelet rescan, gloves off.

Then there’s the revolving door of people who come unannounced and start talking. The leukemia resident, the full leukemia team, orthopedic docs, neurologists, supportive care (a.k.a pain) team. social worker, food people, physical therapist, patient care technicians, floor sweepers, garbage emptiers, computer fixers, transport people—all against a backdrop of loudspeaker announcements, hallway chatter, and beeping IV pumps. Noisy, interrupted, and never ending because the roommate gets it all too. We share a door to the hallway but it never closes. What’s the point. There is no peace.

There are field trips though, little splashes of excitement when I leave my floor. I am wheeled away for my echocardiogram (good to go!), brain MRI (all clear, phew!), PET scan (leukemia in other spots, sorry!) chest CT scan (clots on your lung, sorry!) leg ultrasound, full body MRI (tumor hasn’t shrunk, sorry!) and eye oncology workup (passed with flying colors!) I pathetically look forward to these excursions that require an elevator. I am downright disappointed when they tell me my bone marrow biopsy will be in my bed.

Every test result is a potential sentence to more days in the hospital though. Like my EKG every morning. If my heart isn’t healthy enough for the chemo, I can’t get it. That then delays my treatment and prolongs my stay. I wish I could study for these tests, but I have no control over how my body performs.

Better than a Russian prison

I have all the time in the world to think about, well, everything. When my mind strays to the life I’m not living, it hurts too much. So I try to trick myself into thinking about something way more terrible, like the Russian prison I’ve conjured up in my head. It makes my hospital accommodations seem palatial. I still have a pillow and can FaceTime my kids, after all. ‘Russian prison’ becomes my mantra. Lumpy sagging mattress? Better than a dirt floor. No fresh air? Better than a windowless cell. Snoring roommate? Better than solitary confinement (maybe?). It’s all relative.

But then one day it actually feels like a Russian prison. I’m having a full body MRI and need to lie completely still on what feels like a steel plank for 75 minutes. The real issue is the 9 out of 10 chainsaw pain in my leg. I know how critical this scan is though so I somehow hold in my agony. The ultra loud cacophony of clicking ticking blender jackhammer leafblower sounds pulsate through the claustrophobic space. It’s one of the longest and most excruciating hour and fifteen minutes of my life.

When they finally slide me out of the tube, I lose it. I start sobbing. It’s as if I’m releasing all the pent up pain and focus that was required to not move. By the time I’m back in my room I’m having some sort of panic attack. Steve later tells me I looked like the Incredible Hulk transforming, clenched fists and vein-popping arms and all. I’m wondering why no one seems to care that I’m dying. I can’t breathe. I throw up. I beg for air. My leg is screaming. I plead for air again. Suddenly there are 12 people staring at me. Someone puts oxygen in my nostrils. Someone injects something into my PICC. I slip under. When I wake up hours later they tell me the tumor in my femur is still the same size as the day I got there. I reach for the barf bag.

The three delirious days that follow, I’m on a fentanyl drip. This is also a royal mess (oops a bit too much opiate magic!) but at least it turns down the chainsaw.

My dream team

My Russian prison only gets me so far. My real secret sauce is my family. Nothing tops seeing my kids, but I only get to see them a handful of times. Steve and my mom lead the charge and my three sisters travel hundreds and thousands of miles to be by my side. One does the cross country trip twice.

There’s nothing for them to do, really. It’s just sitting around for hours, maybe taking a snooze, maybe getting me some ice water. They pass the time with me. The hospital is a very lonely place. I’m still alone a lot, but these visits are my lifeline.

Not pictured are the wonderful cousin who does a tour of duty too, and Steve’s mom, the rock who helps keep our little people afloat at home. I certainly won the mother-in-law lottery—like my mom, Steve’s mom is giving, selfless, and willing to do anything to help us.

Pennsylvania is 41 and unmarried. She’s asked every day about her living situation and family and caregiver help, but she has no one. She’s been in treatment since 2017 and just had a bone marrow transplant. She has a sky-high fever and lies hot and alone all day. Meanwhile I have a loop of family visitors, and half my town is making dinner for my kids and driving them around to help us. How lucky I am, I’m reminded.

Brooklyn, my fifth roommate, is a 40-year-old professor. She’s a good one because she doesn’t use the bathroom and the only noise comes from her partner snoring next to her, occasionally. But one day, as my sister and I are diving into our burrito bowls, Brooklyn has back to back bouts of explosive diarrhea. We know this from the sound of it splattering all over the floor. Twice. We can’t not hear it. It’s right next to us. An army of nurses come in wearing hazmat suits to tackle the smelly liquid mess. It takes awhile. I don’t finish my burrito bowl.

The physical breakdown

This is the least I’ve moved my entire life. Most days I only go as far as the bathroom, about eight feet away.

Blake does the math one day when he visits— 367 laps around the 12th floor is a marathon. Huh, seems doable, I think. We head out. He trails next to me pushing my IV pole. I’m winded by the nurse’s station. I stop to catch my breath. A frail old man passes us. I quickly grab my aluminum sticks and start speed crutching as fast as I can. I don’t catch him. I finish one loop huffing and puffing and stop in front of my door. I sink back into bed. I don’t recognize this weakened version of me. The 12th floor marathon will have to wait.

Every day I look out my always-open door and see my blood cancer peers flying down the corridor. I am the only one on crutches. The only one who needs another set of hands to walk. The only one who has a leukemic blob eating away a huge chunk of her leg bone. The only one with a case the doctors have never seen.

When you keep hearing “your case is so unique” and “we’ve never seen this before!” from the best leukemia doctors in the world, it casts some doubt on their predictions that follow. Even they admit this. If my case is such a rarity, how does anyone really know what to expect? (As I like to clarify for Steve, I’m a realist, not a pessimist. Big difference!)

Fresh air I took for granted

By week three, the stale dry air that’s pumping through the hospital walls becomes suffocating. Now that I really notice it, I resent it more and more. I start dreaming about what it would be like to get a sniff of the outside world. I’d take 100 puffs of dirty diesel exhaust if I could. My nostrils are longing for real, raw, natural.

On day 29 I’m sent to the 11th floor for my fourth MRI, of just my hips and legs. The transporter turns me out of the elevator, and there I see them, two windows cracked open. Stop! I squeal. Please, please let me breathe that air! Please, I beg. He obliges. He turns me 45 degrees and wheels me as close as he can. My one encounter with fresh air only lasts seconds, but it’s a taste. A delicious, tiny taste. A delicious, tiny hope.

Nothing compares to real tragedy

My junior year in college, my friend Blair and I both stop playing lacrosse. With a lot more time on our hands and perhaps in attempt to hold on to our identities as athletes, we hatch a crazy plan to run the Big Sur Marathon. We have no idea what we’re doing. By mile 22, we’re out of gas. We grimace and struggle but most memorably, we start laughing—we laugh and laugh about how much it hurts, all the way to the end. My shot quads would still be on a hill overlooking the Pacific if it weren’t for Blair. She got me over that finish line.

Blair was one of the most beautiful, brilliant and wildly creative people I’ve ever known. She was bold and witty and above all, kind. I looked up to her (literally, too—she was a 5’11” smokeshow.)

In recent years she had been battling a far more vicious and punishing cancer than mine. The depths of her suffering, I will never know. I very much regret that. I thought I had a sense, but turns out I didn’t have a clue.

Blair dies when I’m in the hospital, unexpectedly. I can’t even grasp the news. Just days prior we texted about meeting.. When the world loses a unicorn like Blair, regular folk like me don’t stand a chance. I wish I had done more to listen. It’s a hard lesson to be reminded of. I will try, in her honor, on my way to this next finish line.

A masterclass in patience

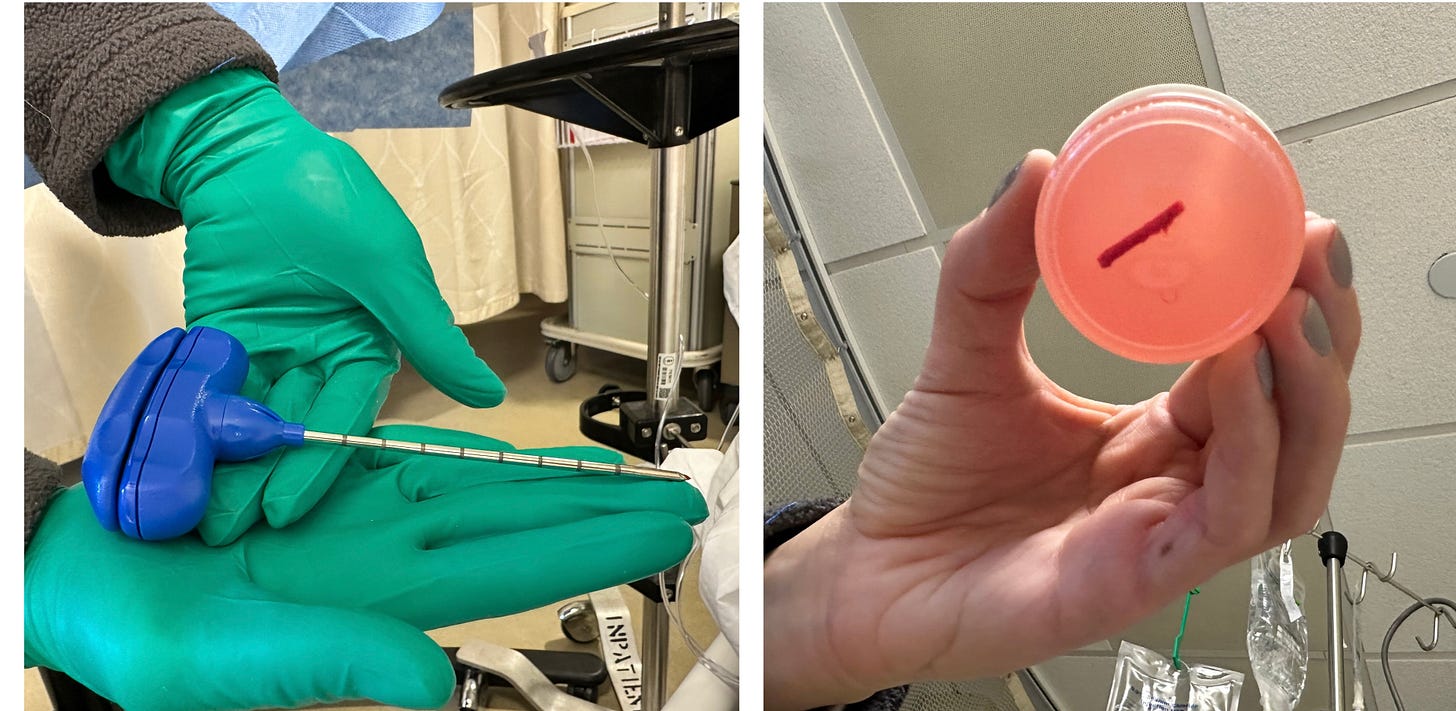

The bone marrow biopsy (along with my mutated chromosomes) drove my exile to the hospital. It’s also my ticket to freedom. It will show whether all of the tumultuous days of treatment are paying off.

I have been waiting for this final exam for over 30 days. so I genuinely look forward to this screwdrivery tool plunging into me and extracting my innermost goods. It’s not a fun procedure, but I would do a million of them to go free.

The last week in the hospital is flat-out torture. It’s by far the hardest part of it all. Everyone knows miles 20-26.2 are where marathons are won and lost, too. But the hospital stay is running a marathon with a moving finish line — a nearly impossible feat. It’s an eternity for the results of the bone marrow biopsy. It’s Thursday when they say Monday could be the discharge date. Getting to Monday becomes all I can think about. Then two days later they say it’ll be Wednesday at the earliest. That’s like telling someone on Mile 25 that the finish line isn’t 26.2, but rather 28.2. There is no strength left though. It feels utterly impossible to keep going.

Then I’m told physical therapy is part of the final exam too. I need to be cleared for crutches at home. Shoot, my doctors only see me lying in bed every day—well I’ll show them! I wait for rounds so they’re in the hallway. “Pssst Stevo, it’s time.” I whisper.

I’m nervous. This is an important performance. We start the lap but my adrenaline sends me out too fast. “Slow down, Katie,” Steve cautions. By the time we reach the team, I’m panting. So I hold my breath and muster up my best crutch strides. ‘Nice to see you up and about, Kate,’ says the Attending. I get a thumbs up from the resident. Damn straight they’re clearing me. I start breathing again back in my room. I have to lie down for the rest of the day.

Then Steve tells me Shane has a fever. Shit, he visited last night. No way they’re letting me out if I’m sick, I brace myself every time they take my vitals, and let out a huge sigh of relief when I don’t have a temperature. I suck on ice cubes to try to skew the readings.

The euphoria of freedom

It‘s five weeks to the day when I get out. As they roll me through these automatic doors, I inhale the crisp and pungent NYC air. I am Tim Robbins in Shawshank Redemption. I just crawled through five weeks of (metaphorical) shit, and I am gloriously free. Tears well in my eyes. I will never, ever forget this moment. I am going home.

What ever role DNA plays in writing and giftedness as well as grit and determination clearly resides in your first l-born, Blake❣️

-Step-Grandpa to Blake

Kate - First, you are a wonderful and talented writer. Thank you so much for bringing me into your world in such a vivid way. So. so difficult but your spirit is so beautiful. Thinking of you all the time and sending you best wishes as the healing and the fight continues. Love - Nicole